About Peter Gluckmann

Echoes of Aviation’s Romantic Age

By Louis Helbig, September 2025

In late June 1953 a portly 27-year-old named Peter Gluckmann — leaning against the bar at the Royal Aero Club in London, England — caught the attention of 69-year-old Fred Sigrist. The one time chief engineer of Sopwith Aircraft and a founding director of Hawker-Siddley had something in common with the young aviator — crossing the Atlantic in a small plane. Sigrist wanted to learn how this young man had succeeded where he had not.

For a while, just after the Great War, the world’s attention was fixed on the then astronomical £10,000 Daily Mail prize for the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic. Sigrist managed the ‘Sopwith Atlantic’ — a converted WWI bomber — crewed by Australian Harry Hawker & Canadian Kenneth Grieve. Alas the ‘Atlantic’ ditched about half-way across. The crew survived, were feted by massive crowds at Kings Cross, London and were even given a £5,000 consolation prize.

We can imagine what Gluckmann shared with Sigrist. The details are recounted in the 1954 FLYING magazine article ‘California to Germany, Roundtrip’ (posted here). Sigrist would have known that Gluckmann’s Luscombe 8F N1838B was the smallest aircraft to have crossed the North Atlantic to that time. He would have also known the risks.

Fred Sigrist, famous English industrialist with the might of the UK’s most important aviation company behind him, would have learned that Gluckmann pulled off his feat without sponsorship or external support. He did it on his own dime. There was no prize waiting for Gluckmann.

It was a chance, most remarkable meeting. It was an overlap of two different eras.

Gluckmann’s accomplishments came just after the romantic, inter-war period of aviation when the world watched men and women — cast as heroes — fly ever further and faster over continents and oceans. Blériot, Curtiss, Post, de Saint-Exupéry and Earhart, to name a few, were household names. The most famous, Lindbergh, had crossed the Atlantic only 16 years earlier.

Like Lindbergh, Gluckmann was unknown before his flight. Unlike Lindbergh Gluckmann never became a household name. An afterglow, though, of that grand era of aviation adventure did cast a light on Gluckmann. He carried on with a passion for long, often record setting, flights and found various ways to leverage the increasing public attention he received. He kept flying, ever further.

continued ...

Prying that leverage did not take long. Later in 1953 Continental Aircraft Engines ran an ad featuring Gluckmann and Luscombe N1838B. They capitalized on that recent past, likening Gluckmann’s flight to that of Lindbergh’s. Gluckmann, too, appears to have done well by his endorsement. The aircraft logs show the installation of a new engine and accessories only two months after Gluckmann returned to the US; we can assume that was in payment. That engine is still in the plane.

“Jedermann”, a Somebody - Making History

Sigrist likely did not know of Gluckmann’s unlikely background. He was a German-Jewish refugee — and a recently naturalized American. Fourteen years earlier, in January 1939 — as a 12, almost 13-year-old — Gluckmann had, with his family, fled Berlin and the Nazis for London. He emigrated to the US in 1947.

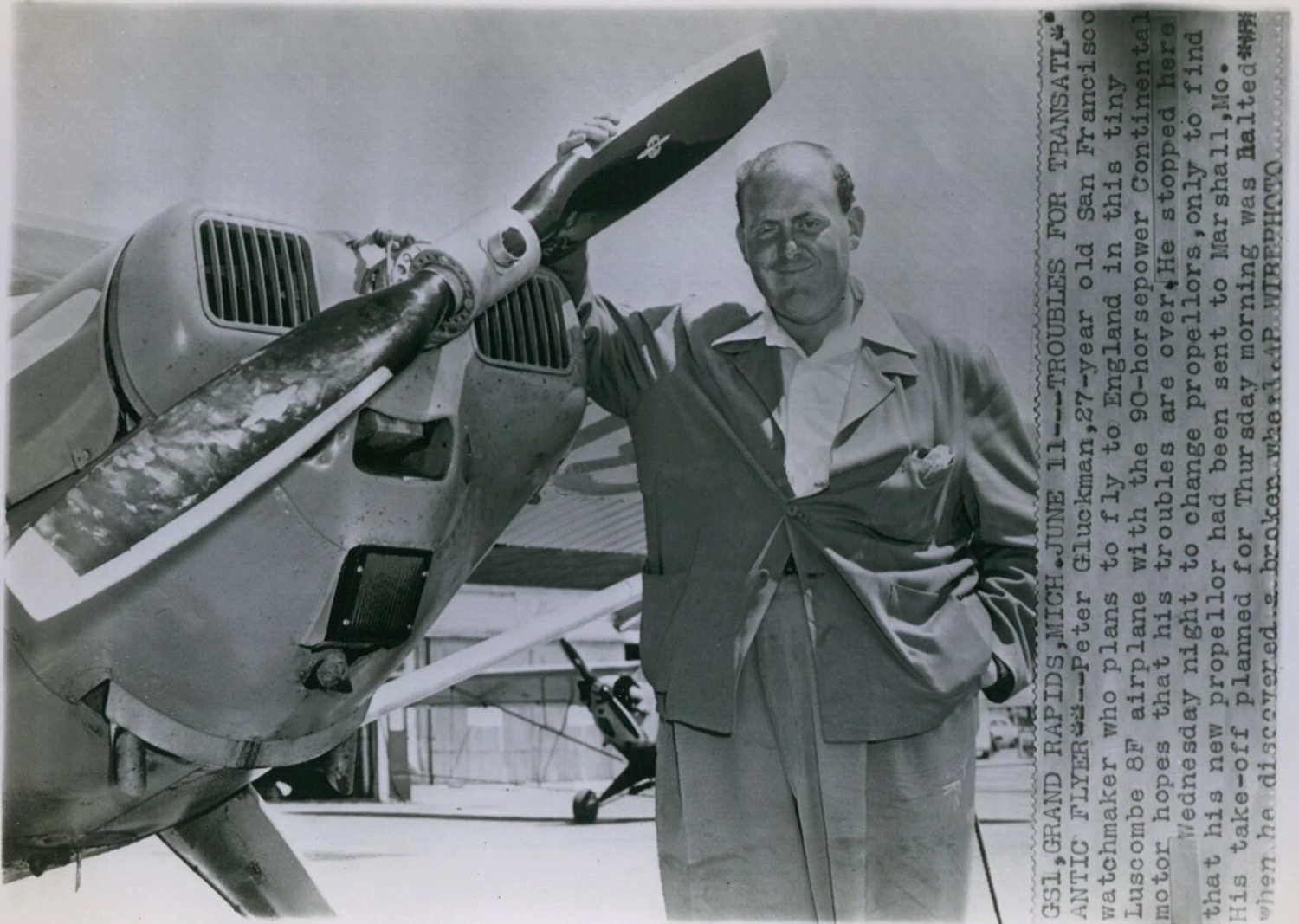

Peering at the photos of Peter Gluckmann at the start of his flight to Europe, gives one the impression of him being a “Jedermann” a German expression (which he would have understood) denoting an average person. The photographs with his plane in San Mateo, CA before leaving, and the picture a few days later in Grand Rapids, MI, rumpled and portly with greasy trousers and an ill-fitting jacket (having just replaced the propeller) fit that bill.

He is plagued by a lack of money. He said about flying to London with his own aircraft,“I couldn’t afford it any other way.” In Goose Bay, just before he sets out for Greenland, he does wear a tie - and even a kerchief in his coat pocket - but neither seem to suit him. He looks part worried — for good reason — and content with the company of the American servicemen helping him with his plane.

His look begins to change on his arrival in England. In the remarkable press photo of him greeting his mother in London, he looks incredibly happy, sharply dressed, but still very young. His mother, it is reported, is not as impressed by his flight as by his size. She says, of his 260 pounds that, “he is too fat! I’m going to feed him lots of salad.”

Gluckmann notes in FLYING magazine that his departure airport, San Mateo, was closed in his absence and he had to land elsewhere in San Francisco. It’s not a stretch to think that he both returned to a different place, and as a different person.

In the photos of Gluckmann that follow, with ever larger and more sophisticated aircraft — all modified for long distance flight — he exudes ever increasing confidence, maturity and charm.

continued ...

By 1958 Gluckmann, “dieted away 80 pounds to enable him to carry more gasoline,” but he appears not just motivated by this aviation practicality. He is always sharply dressed in well fitting, quality clothes, waving and posing confidently for the press.

Transformed from a “Jedermann” to a somebody. In 1953 his trans-Atlantic plans garner some press attention before he leaves Labrador for Greenland. In the UK the wire services really pick up the story and his feat is recorded in newspapers around the world.

This cycle becomes a pattern, and the press gives him ever more attention as he racks up ever more frequent, globe trotting, long distance flights. From his appearance, and his eventual success at raising funds through commercial endorsements — and even getting into the business of manufacturing aircraft parts himself — , Gluckmann, the somebody, becomes well skilled at cultivating a persona — The Flying Watchman.

There are differing ways of trying to explain Gluckmann’s original motivation, from the accounts and evidence that still exist. His family is clearly on his mind. His first flight is to his parents and brother William, in London where they remained after they fled the Nazis. He visits them repeatedly in the next years, as he does other relatives in West Germany, Israel and South America.

A 1953 press clipping implies he made the trip urgently to visit his ailing father. The aircraft’s logbooks & documentation suggest he had been considering it years earlier. In 1950 Gluckmann rebuilt his instrument panel (to his own specifications) for IFR (instrument flight — much of that is still in the aircraft now). The extra fuel tanks for the flight were installed in 1951

Cost also appears to have been an important factor. He paid $1,800 for his Luscombe in 1949 or 1950, however the major modification documentation of the aircraft in 1950 and 1951 (“337s”) show a bank and then a certain Perry Taft as legal owners of N1838B. His name is finally on the documentation in 1954 when the extra tanks are removed.

In the FLYING article about the flight to Berlin the price of lodging, costs of food and fuel are a constant theme. Some events are described as "highway robbery” others as a “free ride.” Before he leaves he estimates the flight will cost him about $300 for fuel and incidentals. The final cost is $400. In London, when asked about returning to the US, he says: “How will I get home? The same way I came, I couldn’t afford it any other way.”

continued ...

It is unfortunate that only an abridged version of the full 72 pages of transcription of Bud Dennison’s interview of Gluckmann were included in the FLYING article (perhaps these notes still exist somewhere?) for it well seems that some of the kind of detail we would now think important were largely omitted. And, as the editorial cover makes quite clear, there is also a certain political bias in how the material was presented. This was the McCarthy era and the fingerprints of that are on the editor's typewriter keys.

A Witness to History

Gluckmann’s life, like that many millions of others, reflected the turmoil and upheaval before, during and after WWII and its aftermath, the Cold War.

Gluckmann clearly really wanted to return to Berlin. He made the effort in London to obtain a letter of permission from the American ambassador to the UK to fly to the now occupied city of his birth (occupied by the four powers, the US, Soviet Russia, France and the UK from 1945 until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and Germany was reunified in 1990). En-route, when he landed at the US base in Hannover, he was initially forbidden by the commander from continuing to Berlin. Gluckmann was persistent. He showed them his letter and they let him fly. Gluckmann says, “they (the base) couldn’t understand how I got permission—but I did.”

Peter Gluckmann’s flight to Tempelhof Berlin via the Central Air Corridor was yet another first: “I was the first civilian flier to cross the corridor between East and West Germany.” In fact, it is quite likely that he was the only private, civilian aviator or “sport pilot” to fly to Berlin before reunification. Berlin was a ‘no-go’ for German pilots and airplanes. Outside of the military the only civilian aircraft to enter West-Berlin were commercial airliners from the US, France and the UK.

Was Gluckmann’s motivation a natural one, of returning to one’s hometown to wander through neighbourhoods that should be familiar but turn out to be much bigger or smaller or just plain different than one’s childhood recollections? In West Berlin he visits the house where he had been born. But, “it had been bombed,” he said, “and there wasn’t even rubble left —only grass growing on an empty lot.”

Did his identity as a Jew play a role? In 1953 he is described as an enthusiastic member of the Congregation Emanu-El. Did he return, simply because he could, having been driven out of his home and culture by a despotic, terroristic regime bent on exterminating him and anyone like him? His father is reported to have been in a concentration camp and to also have died (the accounts are inconsistent; there is a 1956 photo of Peter with both parents and brother in London). Gluckmann visits family graves and reports that, “the names have been obliterated from the stone — just as was done with all the Jewish graves.”

continued ...

Was his motive more romantic, wanting to see Tempelhof airport, which if he was interested in aviation at an early age - which we can assume he was, as he obtained a pilot license only a year after arriving in America — would have loomed large as a place of wonder for a 9, 10 or 12 year old?

Or was the Tempelhof airport a goal because it loomed so large in the Cold War struggle between West and East?

Tempelhof had been central to the Berlin Air Lift — just four years earlier — by which the US and its allies overcame the sixteen-month Soviet/Russian siege of Berlin. Now, just days before he landed in Berlin — while he was flying to Europe — the Russians and their tanks crushed the June 17, 1953 uprising in East Berlin. That was in the headlines.

He would have directly witnessed the acceleration of the “Republiksflucht” where hundreds of thousands were fleeing the German Democratic Republic for West-Germany. In May 1952 the East/West German border was sealed and the only remaining escape was to West-Berlin. When Gluckmann was at Tempelhof thousands of refugees per day were being flown to West Germany on military and civilian planes.

Gluckmann says he had his camera at the ready while flying along the 20 mile wide air corridors to and from Berlin (the Central Air Corridor from Hannover, the Southern Air Corridor back to Frankfurt) and was disappointed to not see any Russian aircraft.

Did he pick up on the despair, even in West-Berlin that followed the war? Many West-Berliners believed that America would eventually abandon the city to the Soviets and left for the safety of West Germany. It was still a city of ruins. The economic and political conditions, while better than in the East were still bleak. Between the rubble, people were growing potatoes and raising chickens to feed themselves.

We will never have complete answers to any of these questions. Whatever his thoughts and feelings were, Gluckmann only stayed for 20 hours and stated that, "Berlin was not a nice place to see.” One can imagine his anguish of seeing the ruins and destruction, the neighbourhood of his childhood laid flat, the empty lot where his home once stood. Being in Berlin would surely have been a harsh reminder of the Nazi’s legacy. Surely, many, if not most of his friends and kin were dead, either murdered by the Nazis or killed in the course of the war.

continued ...

With more questions than answers - and questions now that would be very different than the questions then - Peter Gluckmann is a witness to, a participant in and a maker of history. His experience, while particular — his accomplishments were extraordinary — gives us a unique window into a time and a set of circumstances lived by millions of fellow travellers, before, during and after the Second World War, and its lingering aftermath, the Cold War.

The Flying Watchmaker, Circling the World

While it might be arguable whether Gluckmann was a “Jedermann” before he left — within a year of arriving on the Queen Mary in New York in 1947 he opens a successful watchmaking & repair business in San Francisco, soon has a pilot license, acquires the Luscombe, teaches himself to fly “blind” (on instruments) and then began planning his flight to Europe in 1950 or 1951 — he wasn’t a “Jedermann” when he came home.

After his flight he became increasingly well known as the “Flying Watchmaker,” and in quick succession he obtained title to his Luscombe and then purchased a series of larger and more sophisticated aircraft to act on his enthusiasm and ambitions as long-distance, record setting aviator.

In 1954 he still seems to be suffering financially. Gluckman is reported as “hoping that an ‘angel’ may come forth. He needs an individual, an oil company or some other commercial firm,” to assist a planned flight to Israel (completed in 1956). Those funders do materialize and he uses his growing recognition to finance his globe-spanning flights.

There are ads of Peter Gluckmann endorsing engines (Continental) aircraft (Beechcraft) and two oil companies (Bardahl and Chevron). He forms the Gluckmann Aviation Company and use his technical skills to design, certify and manufacture an auxiliary fuel pump for Beechcraft Bonanzas. In 1958 he writes “Four Continents in a Bonanza,” for Flying magazine in which he embeds a product endorsement for Standard Oil

continued ...

In 1956 the Luscombe is left behind. With a larger, faster Cessna 190 (also with extra fuel modifications) Gluckmann flies clockwise from Idlewood, NY to Iceland, Europe, Middle East, Africa and South America. There are a number of firsts, including the first direct flight between Israel and Egypt. The Cessna 190 is named the “City of San Francisco,” as is at least one of his next aircraft.

In 1957 he flies from San Carlos (near San Francisco) to Honolulu return, for a “vacation” with a Beechcraft Bonanza becoming the first to do so in small single engine aircraft. 1958 sees him criss crossing the Southern Hemisphere this time counter-clockwise to Chile, across the Andes, to Africa via Brazil and then on to Europe and back, again, across the North Atlantic, to Goose Bay.

Peter Gluckmann was not alone in his aviation exploits. Others were also accomplishing first, long distance flights between continents and across vast distances. One of Gluckmann’s “competitors” was Max Conrad who may have inspired Gluckmann with his flight of a four seat Piper Pacer to the UK in the early 1950s.

In 1959 Gluckmann purchased a Meyers 200A aircraft and very intentionally set out to meet the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) criteria for a record flight. Despite having various mechanical, weather and other issues that slowed his flight, he became the first owner of the ‘Round-the-World Eastbound in a piston powered aircraft’ record on September 20, 1959.

Two months later he delivers a shiny new Cessna 172 from Oakland California 2,400 miles to Honolulu, Hawaii.

However much Gluckmann gave the impression that his flying was routine, the risks he took were enormous. In the press clippings Peter Gluckmann comes across as matter of fact and nonchalant about his accomplishments. He describes most of his flights as quite normal and everyday when they were anything but. Parallels are drawn between his skill and attention to detail as a watchmaker and those as a pilot. Judging by his ability to garner press attention and secure sponsorship and support from aviation manufacturers, it seems he quickly learned to create an outwardly confident, competent and charming personality.

continued ...

There is evidence of some discrepancy between that careful, detail oriented public persona and his actual flight preparations. In 1954 he flies across the continent (in the Luscombe?) unaware that Canadian regulations have changed forbidding single engine flight across the Atlantic. He is forced to leave his aircraft in Gander, Newfoundland and carries on in a commercial airliner.

On the 1958 flight through South America, Africa and Europe he plans for and lands at a non-port of entry airport in Mexico, is missing a navigation chart and local airport frequencies in France, and knowingly crosses Europe and the Atlantic with structural wing tip damage (from taxiing with overloaded tip tanks in Brazil).

There is a first hand account from his US military weather briefer in Tokyo in 1960 that bemoans his, “almost total lack of navigation and radio equipment,” before he sets out across the Pacific with only a Mae West (a life jacket) and no life raft. The briefer quotes Gluckmann’s response to their concerns. “Flying is now my love and any man wants to give for his love. It is my dream to do this that no other man has done. I know I must take my chances to make this dream come true.”

Shortly after setting his 1959 FAI record, Gluckmann was in the air again, this time to break Max Conrad’s very recent with light-plane non-stop flight record. Gluckmann’s first attempt, in a Beechcraft Bonanza specially modified to carry enormous amounts of fuel, was from Hong Kong with a flight plan for New York via the Alaskan Aleutian Islands. That flight was aborted due to poor weather and he returned to Tokyo.

Gluckmann re-planned the record attempt from Tokyo via Hawaii to the mainland USA.

At 7:00AM on April 28, 1960, he took off from Tokyo. He and his airplane were never seen again.

A Personal Note on Luscombe C-FEPO & my Research

By Louis Helbig

I purchased Luscombe serial number 6265 from Richard Marcus in Komoka (near London), Ontario in 2013. Richard had purchased N1338B, in pieces, in Akron, Ohio and rebuilt it in Canada in 1989. It received registration C-FEPO. He only realized its trans-Atlantic history when he had it back in Canada and examined the documentation.

I have flown C-FEPO to both coasts in Canada and as far north as Fort Smith, on the MacKenzie River in NWT. In June 2017 I quasi recreated at least part of his flight, by flying to Happy Valley Goose Bay, Newfoundland Labrador. On my final approach into Happy Valley I couldn’t resist excitedly telling air traffic control (ATC) that my plane had actually been there sixty-four year earlier with Gluckmann at the controls. Not unlike Gluckmann, I contacted the local media and they wrote a nice story about the Luscombe and Gluckmann (Labradorian).

In the years that I’ve flown C-FEPO, sitting in the cockpit exactly where Gluckmann did in N1838B, hands on the same control column & seeing the world unfold through the some windshield (even over some of the same scenes, like Goose Bay & Niagara Falls), I’ve often wondered what Gluckmann was thinking & feeling. Conversely, I’ve also wondered how Gluckmann would have reacted to what I’ve lived & experienced with ‘our’ Luscombe.

Besides the connection of ownership, I have a connection to the history he was witness to. My late father grew up in Berlin (in the suburb of Wannsee, one of the checkpoints for the Central Flight Corridor to Berlin) and was — aged 11 at the end of the war — a beneficiary of the Berlin Airlift. He bore some scars in later life from his childhood experience of the war. But, like Gluckmann, he was also an enthusiastic aviator. My first flights, and my best times with him, were beside him in his small plane, a 1946 Aeronca Chief.

I visit Germany and my relatives regularly — something Gluckmann could not do. Many of them are deeply concerned by the present turn in our history. They well remember — it is still a lived experience for the very elderly including my aunt, my father’s older sister — the horrors of World War II and understand only too well the parallels to our time.

continued …

In the world of aviation preservation there is often a fixation on ‘war-birds’. That is aircraft, most often from WWII, that were used in active duty by one or another armed force.

N1838B/C-FEPO is not a war-bird. But, N1838B did —with Peter Gluckmann — bear witness to the consequences of war. Gluckmann’s all too short life story was inexorably connected to and formed by the tumult and suffering of the Second World War and its aftermath, the Cold War. N1838B carried Gluckmann as a ‘Zeitzeuge,’ a contemporary witness, to things and events over which he had no control but out of which he made the very best.

Peter Gluckmann’s use of N1838B hones near to that spirit of aviation embodied by Richard Bach or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. I would like to think of my own use of C-FEPO in a similar light. Taking photographs from it, responding to what the airplane suspends me over, carrying me over the magic carpet that is our earth’s surface from a thousand or a few thousand feet up.

There is something zen like and compleat, a kind of magic in being suspended in space until the weather changes or the fuel runs low and one needs to land. Whether to get from here to a faraway place, as Gluckmann did with N1838B, or just to hang out in the air for a while, as I did with C-FEPO, this airplane has carried its custodians to some very special corners of the human experience.

I have been to Tempelhof Airport in its newest incarnation as a huge, open-air park in the middle of Berlin. Standing on one of its long, wide asphalt runways — the markings, taxiways, and signage are still intact — I could well imagine Gluckmann landing here, and I could well have imagined myself landing there too.

Tempelhofer Feld is Berlin’s largest public park. It has free access to anyone, a place where “Jedermann” can be themselves, just a little away from the bustle of Berlin.

When I last visited, I saw children flying kites. Their laughter and amazement, their pure joy of seeing their kites wafting into and floating on a breeze, reminded me of Gluckmann, that essence of & magic of flying, and his joyous enthusiasm for aerial adventures.

continued ...

Research

The information on this website was compiled from numerous sources. It includes the documentation that accompanied the aircraft and many hours of internet research over the years. Unlike many older aircraft N1938B/C-FEPO still has original aircraft logbooks, both US and Canadian.

I have waded through countless websites and have compiled scores of screen shots, links and images that reference Peter Gluckmann’s first flight across the Atlantic and his life before and after 1953. The available information has changed over the years. Websites have disappeared, search engine algorithms are increasingly limiting the data one finds, some information has disappeared behind paywalls and lot of what once appeared on blogs/posting sites has disappeared into the maw of social media. On the flip side the web always seem to generate new information. More of the era’s press coverage has been digitized, and particular to this topic, hard copy press photos (from media archives) and advertisements (cut from magazines) are appearing on eBay.

I have tried to document most sources of information consistent with my training as an historian (MSc in Economic History). I know enough to recognize that my sourcing is somewhat haphazard and incomplete (compiling, summarizing and sourcing/documenting information is time consuming, hard work).

I would also like to note that while I’ve made every effort to be as accurate as possible, I’m certain there are many omissions and errors. There are inconsistencies and contradictions in some of the information I have found, but most errors and omissions are my responsibility. I’m certain that anyone choosing to continue researching and documenting the social, cultural, political and aviation history that is the story of Peter Gluckmann and his accomplishments with N1838B and his other airplanes will find much more than I have.