News Articles about Peter Gluckmann, his long-distance flights & Luscombe N1838B/C-FEPO

Nottingham Evening Post, “LIGHT PLANE CROSSES ATLANTIC Lone Flier in Tiny Machine,” June 26, 1953 p.1

A 27-year-old San Francisco watchmaker Peter Gluckmann landed at Renfrew Airport to-day after crossing the Atlantic in what is claimed to be the smallest aircraft ever to make the trip.

The plane, a blue and gold Luscombe, has a 35ft. wing span, and it is only six feet from ground to cockpit.

Fog prevent his landing at Prestwick, so he flew on to Turnhouse (Edinburgh), but because of poor visibility there, turned back across Scotland to Renfrew, where conditions, though not perfect, enabled him to land safely.

“I was worried. There was plenty of fuel in the tanks, but I was afraid Renfrew would also be fog-bound,” he said.

GROUNDED NINE DAYS

The flight started on June 5th from San Francisco. Bad weather kept him grounded nine days in Greenland.

At 9 o’clock last night he left Iceland for Scotland.

Gluckmann who bought the plane on hire purchase, took up flying only four years ago.

The Atlantic trip, his first long flight, was intended as a surprise for his parents, who live in London. The trip was uneventful until he crossed the Scottish coast.

Mr. Gluckmann, a bachelor, was born in Germany. The family left because of anti-Nazi sentiments.

As for the flight, Mr. Gluckmann said, “it was entirely uneventful; just another flight.”

Louis Helbig note: the euphemism that Gluckmann’s "family left because of anti-Nazi sentiments” is rather jarring given what was known of Nazi atrocities in 1953.

Daily Mirror, “He hops Atlantic to pop in on parents” June 27, 1953

A man living in San Francisco wanted to pay a surprise call on parents in London — so he flew the Atlantic in one of the smallest planes ever to make the crossing.

He is Peter Gluckmann, twenty-seven year old watchmaker. Yesterday he landed his “baby” plane, a blue and gold Luscombe with a wing span of only 35 ft., at Renfrew Airport, Glasgow.

The flight began on June 5 — from San Francisco. From there Mr. Gluckmann, who started flying only four years ago, flew across the States and Canada to Labrador.

Then he flew to Greenland, where bad weather grounded him for nine days before he could continue on his way to Iceland.

The trip, which the bachelor pilot described as “uneventful,” was to have ended at Prestwick. But early yesterday fog made it impossible to land. So Mr. Gluckmann flew on to Edinburgh. Conditions there were just as bad, so he had to fly on to Renfrew.

His parents, who live at Finchely, London, first heard of their son’s flight when he telephoned from Renfrew airport.

And Mr. Gluckmann’s own comment on his marathon journey in the tiny plane was: “It was just another flight.”

THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS, SOME PERSONALITIES AND OCCASIONS OF THE WEEK, July 4, 1953 p.27

AFTER CROSSING THE ATLANTIC IN ONE OF THE SMALLEST AIRCRAFT EVER TO DO SO: MR. GLUCKMANN.

Mr. Peter Gluckmann, a twenty-seven-year-old watchmaker and amateur pilot from San Francisco, landed at Renfrew Airport on June 26 after crossing the Atlantic in one of the smallest aircraft ever to make the trip. The aircraft, a Luscombe high wing monoplane, has a 35-ft. wing-span

The Aeroplane, London, July 10, 1953, p.63

CORRESPONDENCE

Groundabout - Atlantic Antic

The Aeroplane, London, July 10, 1953, p.63

CORRESPONDENCE

Groundabout - Atlantic Antic

An interesting meeting in the Royal Aero Club bar was that between Peter Gluckmann, naturalized German-American private owner, who had just made the latest Atlantic solo flight via Greenland and Iceland, in a Luscombe, and Fred Sigrist who, as a director of the old Sopwith company, had been closely associated with the first attempted crossing, when Harry Hawker and Mackenzie Grieve had to ditch their Sopwith biplane half-way across, alongside a small ship which had no radio. Gluckmann, a watch expert, prepared the engine himself and had faith enough to hang a notice on the door of his San Francisco watch business:: " Back on July 13," Good luck to his return flight.

Louis Helbig note: A remarkable, contemporaneous overlap of lives lived, bridging a time from before there was aviation to the jet age (Fred Sigrist, then 67 years old was born in 1886). He was the chief engineer behind the success of Sopwith Aircraft in WW1 and was founding director of what became aviation and industry concern Hawker-Siddley.

JEWISH COMMUNITY BULLETIN EMANU-EL July 31, 1953 page 1 & 10

‘FLYING WATCHMAKER’ FETED HERE AFTER RECORD SOLO HOP

Emmanuelites Will Honor Own Member August 18: To Tell of Flight

By EUGENE B. BLACK

As nonchalant as though he had just returned from Los Angeles on a routine mainliner passenger flight, Peter Gluckmann, San Francisco’s “flying watchmaker,”returned home Sunday from a round-trip hop to London, and early Monday morning was back behind the counter of this jewellery shop at 233 Post St. as though he had never been away.

A round of honors was scheduled to follow the official greeting he received at the airport—- a civic banquet Friday in San Mateo and a special night in his honor arranged by the Emanuelites,- young adult group of Congregation- Emanu-El, of which Gluckmann is an enthusiastic member.

According to Sherman Roberts, president of the Emanuelites, Gluckmann will be the honored guest of the group Tuesday evening, August18 at Emanu-El Temple House. He will relate the experiences of his historic flight and will illustrate his talk with his own slides.

“Why does everybody congratulate me—why don’t they congratulate the plane?”Gluckmann asked confusedly as he shook hands with a welcoming crowd at the airport.

Obviously the honor of being the first flier to twice span Atlantic in a tiny90 horsepower monoplane meant nothing to him. He was concerned only with fact that he started out to visit his mother and relatives in London, spent two glorious weeks with them, flew to West Germany to visit other relatives, and returned home to pick up the loose ends of the business he left June 6 when he hopped from San Mateo airport.

“Was I scared at any time?” Gluckmann parried the interviewer’s question.“Yes—several times. My longest flights were12 hours over the ocean and I couldn’t fly too high because my little plane does not have de-icing equipment.

“Once my oil ran down to a quart and I had three hours to go. But if the oil hadn’t lasted the gas wouldn’t have either—so?”

“Are you a fatalist?” he was asked. “What’s that?” he countered.

No Fatalist

The amateur flier shook his head when the meaning was explained.“Not at all,”he countered. “I believe care and efficiency can prevent misfortune. I watched my plane and I studied my course.You see, I’ve studied the mechanical side of flying, too.I do the mechanical work on my plane also.”

As he spoke, Gluckmann was wiping off his delicate watchmaking and jewelry repair tools. Again and again he dropped his rag to shake hands with people who trooped in to shake his hand. He was back in his shop long before business hours. The first thing he did was to tear off of his show window a sign that read, “Gone on vacation—not fishing.”

Six years ago Gluckmann. who is 27 and weighs 260 pounds, came to San Francisco. He came from London, where his family had traveled from Germany in 1939 when Hitler’s persecution of the Jews forced them to flee. His father already was in a concentration camp.

Two years ago he learned to fly and bought his plane, which he has named “Old Faithful,” for $l,800.“At the time I had no thought of flying to London,” he said on his return. “All that came to me quite recently.”

He explained that after visiting his parents he flew to West Germany to see other kinsfolk. “I was the first civilian flier to cross the corridor between East and West Germany,”he said. “They couldn't understand how I got permission—but I did.”

In West Berlin he set out to visit the house where he had been born. “It had been bombed,” he said, “and there wasn’t even rubble left —only grass growing on an empty lot. I visited my father’s grave. The name had been obliterated from the stone —just as was done with all Jewish graves.”

Cheap Flight

Gluckmann's flight cost him between $300 and $400—that is the flight itself. He found hotels and eating fairly cheap, and as for airport charges, they were less than San Francisco garages, he said. His final hop on the flight of 18,000 miles was from Reno, where a jackpot from a slot machine financed his last night’s room rent and meals.

Over Sacramento he was picked up by eight Civil Air Patrol planes and escorted to the local airport. There a crowd of several hundred people awaited him. Mayor J. Herschel Campbell of San Mateo presented him with a two-foot long key to the city and he was warmly greeted by representatives of the San Francisco and San Mateo Junior Chambers of Commerce.

“The Atlantic is a pretty big body of water,” Gluckmann said in recounting details of his trip. In the plane on the long hop he carried a rubber life raft, a parachute, an SOS radio, a Mae West life jacket and an extra tank holding 60 gallons. This gave him a total of 90 gallons for the long ocean hops between Greenland, Iceland and Scotland.

Louis Helbig note: some of what is recorded in this article is contradicted by other reports. He is quoted here that his father was dead and buried in Berlin. Several other 1953 articles report Gluckmann travelling to London to be with ill father and to see his parents, plural. In a 1956 press picture identifies his father, mother and brother William in London. In 1958 he writes in FLYING magazine about his parents driving to Croydo airport in London to meet him. Were the desecrated graves he visited in Berlin those of his grandparents or other relatives, or was he just misquoted?

(That 260-lb. Peter Gluckmann, an amateur pilot of five years flight experience, last summer flew his 90 hp lightplane from the Golden Gate to Berlin and return without causing a ripple in press headlines, testifies to the casual acceptance of even the most phenomenal achievements in the field of aviation.

Leaving San Mateo, California, airport on June 6, Gluckmann covered 14,000 miles in 188 hours of flying, only to find upon his return a few weeks later that his home airport no longer existed. His second-hand Lucombe plane and its sturdy little Continental engine had performed flawlessly ... as had Gluckmann himself.

Yet let it not be thought that the trip caused no heart-burnings. There was that $14 charge for a hotel room overnight in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and a $7 charge for a cot in the De Gink hotel at Keflavik. There was an instrument let-down, Gluckmann's first, at Iceland, and a plethora of discrepancy between weather forecast and actual conditions.

There were bright spots, too ... that 70-cent box-lunch provided by the Air Force was a honey. The Icelanders were tops in hospitality. There was no landing fee charge at Greenland's Bluie West I on the way home.

And when Peter arrived over Sacramento on his way home there was a formation of good friends to provide an escort to the final landing. Things like that loom big to a lad who fled Hitler's wrath and had to adopt a new country. It's good to be free and have sturdy friends.

Gluckmann's story, as tape recorded by "Bud" Denison in a bull session one night in San Mateo, covers 72 typewritten pages and we haven't space for all of it. However, we wanted the story in Gluckmann's own words, so the following excerpts are used.

Make no mistake about this Gluckmann. He's quite a guy... competent, cool and airwise. And if you need your watch fixed, stop and see Peter about it. His shop is located at 233 Post Street, San Francisco. He's good at watches, too.—Ed.)

TOGGLE BELOW TO OPEN TEXT.

Flying Magazine, January 1953, p.15

We’ll start out with the airplane - which everybody knows is a ninety hp Luscombe. Preparing for this trip involved a few problems. First-the extra gas. I had considered building an extra tank which involved a number of problems and so I wrote the Luscombe factory asking them for advice and help. They came back with the wonderful news that they had some tanks they were prepared to sell me at $15 apiece. I had to convert these tanks into a fuel system because when I got them they had some very large holes in the bottom and several other holes which had to be plugged up. The tanks fitted right into the wings on the outside of my present 15-gallon nylon bags.

My next problem, and of course a very important one, was navigation. There is on the market a Bendix surplus radio compass which could, at that time and I think can still, be purchased quite cheaply. I had this installed at San Mateo Airport at the Fred Baker radio shop. The radio compass has the disadvantage of being very heavy — the whole installation weighed about 65 pounds.

There was one more problem-oil. My regular oil tank holds five quarts and I decided that I would just leave that alone. I had an extra custom-made instrument panel made. I designed it myself, with a view of easy blind flying for an amateur. My instrument experience is quite is limited. I had several lessons here and I knew I could fly the plane for short periods on instruments, provided, of course, that I didn't get into any rough weather and provided I didn't have to make any instrument let-downs to very low ceilings.

I also put on a shoulder harness. This was not so much for the usual reasons for safety against forced landings, but more a matter of comfort for me when flying in very hot weather. It was nice to have the shoulder harness to keep me from bumping my head against the roof every two minutes.

In the end, the total capacity of my plane was 90 gallons and since my usual fuel burning was about 5 to 5½ gallons an hour I felt that I had 15 to 18 hours' range. Actually, I found out later that due to the increased weight and probably also due to the high octane gas, my plane burned lots more fuel. It usually averaged about 6 to 6½ gallons an hour. So I still had about 14 to 15 hours' range. It was still quite safe.

And now for the flight itself. I drove down to the airport quite early to load up my plane. I had a fairly large suitcase that weighed about 40-50 pounds. I didn't hinder myself as far as baggage went, because I felt that if I had to save every few ounces, I don't think I would have undertaken the flight to begin with. I felt quite confident that my plane could handle whatever I put into it and maybe some more on top of that. And, of course, it proved to be right. After loading my plane up I had the problem of my emergency equipment. I carried a one-man rubber life raft. It's one of those affairs where you pull a cord and the thing inflates itself in five seconds. At least, I hope it does. I also carried a transmitter with all the stuff that goes with it, such as the balloon and a hydrogen generator to inflate the thing.

I got off at about 4 o'clock in the afternoon. After stops at Fresno and Bakersfield, I got to Needles, Ariz. about 11:30. That's where I had my first experience with the press, in spite of the late hour. I had disclosed my flight plan previously on the radio and I went into the office to call a taxi and they said, "You're Mr. Gluckmann—we've got a couple of telephone calls for you." They were kind of grinning at me because of course a flight from the coast is about the same as driving your car around the block once. For the newspapers to call up and say what kind of a flight did you have sounded a little silly to those experienced CAA boys. But I learned to have a lot of respect for the press, because just about any place where I landed it was the same. When they want to get hold of you, they get hold of you.

At Grand Rapids, I had the only trouble on my trip. I asked the mechanic in Grand Rapids if he'd just have a look at the left wheel.. I felt pretty certain that the brake shoe was touching, but they took the wheel pan off and to my surprise I found that it was the wheel itself had broken and the magnesium casing was just sticking beautifully to the tire. I was really lucky that I discovered this because, well—if I had discovered it in Greenland, it would have taken me an awfully long time to get a new wheel. Chances are the casing would have poked into the tube and the tube might have blown, and it could have turned me upside down which, in turn, with a full gas load, could have been very embarrassing.

After clearing Canadian customs at Windsor, Ontario, I flew on to London, Ontario, where I stayed overnight. The following day the weather got a little bit marginal, but I had no real trouble. At Quebec I was beginning to feel that I was getting pretty far out, because gas was be- ginning to cost about 52 cents a gallon, and also fewer and fewer people spoke English. All French.

From Mont Joli, Quebec, to Goose Bay, Labrador, I got my first taste of over-water flying because the Gulf of St. Lawrence at that point is about 50 miles wide. That was also the first time that I tried out my extra tanks. At Mont Joli, I put in 15 gallons in each of the extra tanks— half their capacity, in other words. That was the first time that I had taken off with such a big load, but I was de- lighted to find that I hardly could tell the difference. I took off on one of my regular (Continued on page 44)

TOGGLE BELOW TO OPEN TEXT.

Flying Magazine, January 1953, p.44

(Continued from page 15)

tanks, and when I was out about 15 or 20 minutes, and 3,000 feet over the Gulf of St. Lawrence, I decided to switch over to the extra tanks. I hadn't flown for one minute when my motor started conking. I didn't feel very happy. In fact, I put in my log books "These extra tanks don't feed as well as I had expected." But after jiggling about'a little I found that if I kept one wing a little bit low I could drain the gas out of the opposite wing quite easily. So I just kept right on flying and I had no more trouble.

At Goose Bay, for the first time I refueled with Air Force gasoline. It's really nice gas—115-145 octane; and the price is wonderful-26 cents a gallon.

The Weather Picture

Next morning, the weather forecast was good. Oh, they've got a beautiful briefing service at all these military air- ports. I had told them that I wanted to leave about 8 or 9 o'clock. When you call the weather service they make out a folder for you, beautifully painted, all the different elevations-they have the cloud bases, the cloud tops - everything painted in there.

Icing level, winds to the north, winds this way, that way, the different terminal forecasts-they give you the whole works and no matter whether you're civilian or military they give you the same good service. There was just one trouble. I got this weather meteorologist briefing at every military airport during my whole flight. None of those times did I get one weather forecast which was accurate. Perhaps I shouldn't blame them too much because they're not used to forecasting the weather for a plane such as mine, where it may take 10 hours for me to reach my destination. Usually, of course, they forecast for faster planes, and the weather only has to hold good for three or four hours.

My ETA for this flight was about eight and a half hours. The distance in water was about 850 statute miles. I had a little bit of a tail wind and about six and a half hours out of Goose Bay, Greenland came in on the radio very good and strong. There was no side static and I could home on it. And then in the far distance I saw what looked like land. In fact I put in my log book, "I think I see land." I was very happy.

Of course my past experience in flying should have taught me not to believe what you see but to believe your clock. To my great disappointment as I got closer to that supposed land, I saw that it was a very beautiful colored fog bank extending right from the water up. However, by that time I was receiving Greenland so very strongly on the radio that I thought that perhaps Greenland would be underneath this fog bank, and so I decided to go down underneath it. Well, that was quite a silly decision, as I found out later. I got down to about 500 feet on top of the water. The water was as smooth as could be, and I started out underneath the fog bank, but I don't think I flew VFR for 15 minutes when the stuff went right down and I decided "to heck with this, I'm going up on top." So that was the first instrument flying on this particular trip and when I came out a little bit later at about 4,000 feet on top, my knees were shaking. For about an hour and a half or so, I stayed over the solid overcast and I didn't see anything at all.

Then in the far distance I could see what this time I really thought would be land, and it was. Only this time instead of looking like land—it looked like a fog bank, because it was kind of whitish, which was ice from Greenland.

And then for the next nine days I was in dear old Greenland biding my time. It seems that whenever the weather is good in Greenland, it's bad in Iceland. If it's good in Iceland, it's bad in Greenland. It's just about impossible apparently to find a day when it's good in both places.

Circuitous Route

When I finally took off I had good weather reports. I flew out of the fjord and intended to stay VFR right around the Cape of Greenland and then head for Iceland. Heading around Greenland meant lengthening my trip by about 150 miles.

The moment I got out I saw that there were clouds hanging outside right on top of the sea. So I started to climb over the stuff, which wasn't very difficult. Then I guess I got a bit cocky because at about 4-5000 feet, I could look clear across the top of Greenland, the plateau, and I thought—this isn't half as difficult as these people make you believe; you don't have to have 10,000 feet. I can get across at this altitude. I could see the horizon in the distance beyond Greenland just as clear as could be, and so I made a 180 and went right across that stuff. On top of Greenland there was no overcast at all - the sun was shining. After I had reached about 5-6000 feet looked underneath me and I was very startled to find that the shadow of my airplane was just about the same size as a full plane and then I realized that my altitude, instead of what it looked like, one or two thousand feet, was probably more like 10 or 20 feet.

Well, I didn't try to outclimb the stuff. I made a 180 just as sharply as I dared and got the heck out o f there. I just made it back for the field- that was a pretty nasty experience, and the Air Force officers told me that they even.had one or two accidents that way. Apparently, it's very deceiving and you can't judge your altitude over the ice caps.

I got out of there three days later. I flew at about 3,000 feet elevation along the west coast of Greenland. When I got to the south coast I started out over the open water towards Iceland. And I wasn't gone for 10 minutes when I hit an overcast and had to go to instruments. At that time I still didn't feel like flying instruments, so I went right down to the deck and flew about 300 feet above sea level but even there I couldn't remain VFR. I could see the water underneath me, but I couldn't see ahead at all.

I got disgusted and decided to try and go on top. About half an hour to an hour later I came out at 6,500 feet. From then on for the remainder of the trip I don't think I saw more than 10 or 15 minutes of water.

After I was out about 10½ hours I got very close to Iceland and about 30 miles out I was first able to reach them with my transmitter.

Instrument Landing

About 10 minutes out of the beacon, I suddenly got at the instruments again. I didn't even realize it. By this time it was about one-thirty in the morning and there was a kind of twilight. It wasn't dark but it wasn't light. It was kind of gray, and so I didn't see beforehand the clouds, and before I knew it there I was on instruments again. Around about the same time the guy from the capital radio range came back on the radio and said, "Are you flying VFR or instruments?" I told him I was on gauges, but of course they took it for granted that I was an experienced instrument pilot, and they didn't pay much attention to it. I guess they didn't realize that I wasn’t very happy up there. I had never up to that time made an instrument landing or even approach, and now I knew I had one coming. And then I had had about 11 hours' flying time, feeling a little tired, I wasn't too happy at the idea.

But there wasn't much to do. I asked for immediate clearance to make a let- down, and they came right back and said I could do just as I wished. So I pushed the nose down and closed the throttle partially keeping the heat on, and about ten minutes later- I broke out at about

TOGGLE BELOW TO OPEN TEXT.

Flying Magazine, January 1953, p.45

1,500 feet and I was really delighted. I made a straight approach and about two minutes later I was on the ground.

After three days I got out of Iceland. I again had a good weather report from there to England. The report called for the first half of the trip being bad, the last half being perfect. Well, as usual, the weather report was wrong. This time it wasn't just wrong, it was exactly opposite from the way it was reported. The first half of the trip was beautiful and then as I got closer to England, it was hopeless.

I made pretty good time—a little better than was forecast. Apparently the head winds were not as strong as predicted, and I hit the Scottish coast about an hour ahead of time. However, Prestwick was completely fogged in and had a complete ground fog. So the only thing I could do was scout around until I found and open place. They do have some low frequency beacons over in England and— so I was able to tune into one of these beacons for the Glasgow airport, and when I flew right over the port I was able to make out some white lines, and of course I just landed there.

Scotch Reaction

At Glasgow the airport was officially closed, but seeing from where I came they didn't say one word. The airport manager came out and looked at my plane, shook his head and said, "Now I've seen everything.”

I had only about 300 miles left from Scotland to London but there were thunder showers on the way, and so I couldn't get into London, that day. landed first in what was a so-called secret airport where they build British jet bombers. In the States, I would call that a forced landing, although I hated to admit over there in England that after flying 7,000 miles, I lost my way in the last 200 miles.

In London I visited my parents and also visited the Royal Aero Club, who told me that on that week end they had one of the largest air tours of the year, when a large number of British private pilots were flying their planes over to Deauville in France. They invited me to come along for the trip. Since I was eager to meet British and French private pilots, I accepted.

Later I flew over Belgium and Holland to Germany. While I was in London I had gone to the American Embassy and applied there and got permission to fly over the Corridor into Berlin and to land at Templehof Airport, which is administered by the American Air Force. When I landed at Hanover and told them my intention of flying to Berlin, they were all quite surprised and assured me that nobody, no private plane, had ever flown over the Russian sector before, and that it was quite out of the question for anybody to get permission. They were even more surprised when I told them that I already had permission, and showed it to them. And the next morning I took off over the Corridor to Berlin.

This is not a very long flight-perhaps 150 miles and since the Corridor is 20 miles wide, it really is not difficult to stick to it. I had hoped very much to see some Russian airplanes and I had my camera all ready to take some pictures, but to my disappointment I didn't see any. In fact, I didn't see anything until I got to Berlin. Berlin was not a very nice city to see. I stayed there only for about 20 hours. Then I took what is called the American Corridor and flew from Berlin to Frankfort. Here I ran into a bit of trouble from the weatherman.

When I checked in Berlin I was assured the weather would be perfect all the way. Actually, I had a very, very strong head wind, also very bad weather and I had to start around again amongst hills. When I landed at Frankfort I was about an hour to an hour and a half late, and the American Air Force had already sent out a couple of search planes after me.

I didn't like the idea of these people going out to look for me; and I reminded them that in America it takes at least two hours after a man is overdue on his flight plan before they start looking for you. But they said, "Well, this is different. Over the Russian Corridor they don't mess around. They look for you pretty quick."

Return Flight

I landed on the huge Prestwick airport. I'm quite sure that I could have landed there quite easily with pontoons. The water just splashed on my wings, and they told me that it had been rain- ing there for the last 13 hours continuously

When I was still about 200-300 miles from Iceland, I first made out some kind of lines, which at first I thought were just clouds. As I got closer I realized that it was the volcanoes of Iceland. They are east of Iceland and on the very. easterly shore, quite a distance from the airport.

On this trip my radio didn't work too well, so it wasn't possible for me to home into Iceland until I was 100 miles out. I was quite pleased when I got close to the shore to find that in spite of my dead reckoning all the way I was only about 20 miles off the course. When I was about 10 minutes out of the airport I was able to contact the tower and he had been calling me and apparently they were looking for me on their radar direction finding equipment. Suddenly, I was only about five miles away from the airport-I could already see the place and I was flying about 500 feet when the tower operator came up with the bright remark, "Now I can see you. You're 5,000 feet on top of us, about 30 miles out." And here I was, practically over the airport!

I landed about two o'clock in the morning and they had a lot of jets in there. No hotel rooms. There was one bed, which they offered me at $7 and it was one little camp bed and I just said, "I'll be darned if I'll take this." So at two o'clock I got back into my plane and flew over to Reykjavik. Another tower operator called every hotel in town-no accommodations. So by that time it was close to three o'clock. I got back into my plane, headed back to Keflavik, and this time I settled for the bed. It would have been a lot cheaper if I had taken it in the first place.

Orchids for Iceland

Next day I flew back to Reykjavik and I got to know the airport commandant, and also the president of the Icelandic Flying Club, a bit better. These people were very, very nice to me during all my time in Iceland. That evening they took me out for dinner and showed me the city. They really showed me a wonderful evening. And I would like to say that in all the time that I was in Iceland they never made a landing charge, never a hangar charge. They were the most generous and nicest people you could imagine.

I saw Greenland for the first time about eight hours out of Iceland. There was absolutely no radio contact, but I didn't expect that, due to the magnetic disturbances in Greenland. This time since I had already burned up most of my gasoline, I had decided to fly in a straight line right over the cap to the airport on the west side of Greenland and by the time I hit the mountains there I had about 10,000 feet.

When I was about half way across the ice cap I was barely able to pick up very, very faintly the beacon from the airport. This beacon got stronger quite fast and just about when I was over the ice cap and was able to let down a little bit, I was able to get a homing reading on that beacon and I expected to find the airport way up to my right and to the north. To my great surprise the air- (continued on page 48)

TOGGLE BELOW TO OPEN TEXT.

Flying Magazine, January 1953, p.48

port was just about dead ahead of me. I wasn't ten minutes out. That was the greatest feat of navigation. I only feel too sorry that it wasn't me who could have done this, but the radio compass and the good luck.

Next day when I went to the weather bureau to my disgust I saw that the weather map was just full of little cumulus clouds going to 10,000 feet. It really looked pretty bad. In fact, from their forecast it would have been impossible to maintain VFR flying conditions. I was just about ready to give up when I suddenly thought, to heck with this. They've never been right yet, so why should they be right now. So I took off anyway, and this time I was right.

Free Ride

I landed at Goose Bay without any difficulties and went right up to the tower to clear customs and to pay my landing fee and then I got a very great surprise. When I asked how much, they said, “Well this is a light plane, aren’t you? We were told by some higher authority not to charge you a landing fee this time.”

They prepared another box lunch for me at the U.S. Air Force. For 70 cents they give you two or three sandwiches, can of orange juice, sometimes a can of chocolate drink, a small bar of chocolate, a fresh orange, a small tube of mustard, toothpicks, salt, pepper, about everything. I had the most wonderful deal for 70 cents that one can imagine.

At Trenton, Canada, I cleared Canadian Customs and filed my flight plan for Rochester, New York. In Cheyenne-they had some kind of a rodeo out there. The Air Force operator got me a room, which was quite difficult to get; but the following morning when I asked for my bill they charged me $14 for that hotel room. It was the worst highway robbery I had encountered in all this trip.

Then came the last leg of my trip. I was very happy to get back home, with the exception of a little sadness that I couldn't get back to our own airport, San Mateo, because they had closed that up in the meantime. It went the same way that so many others have gone.

Flight plan was scheduled for my arrival i n San Francisco about 1 o'clock. This time it had to be pretty close, because quite a few friends of mine were to meet me right over the city of Sacramento and they gave me an escort into San Francisco. There were about eight planes, and it was so good to see all my friends again.

To go back a little bit over this trip- the only trouble I encountered was a broken wheel at Grand Rapids. I changed my spark plugs twice.

Otherwise, I had no trouble whatsoever.

I changed the oil twice and I must admit I never even had to tune up my motor. These little airplanes really do prove themselves dependable. If you take care of them and fly them with reasonable care, you can do anything you like with them.

END

TOGGLE BELOW TO OPEN TEXT.

Flying Magazine, January 1953, p.13

ONE of the great social impacts of flight has been its magnetism in stimulation of human imagination.

And what a savior that has been through these years when a creeping socialism has preached regimentation and the elevation of the state over the individual, and the dull doctrine of the dole.

Isn't it true that all human progress... even our great industrial and scientific developments... had their origin in the flaming curiosity of the human spirit? When the Wrights first flew they set up a chain reaction of challenge in thousands of others who were itching for some way to project themselves. And when Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic he set thousands of designers and engineers to work trying to catch up with him in terms of global air logistics. And the catching-up business is the sum and substance of human progress.

The writer, even after a lifetime in aviation, gets a thrill from the editorial desk of this aviation magazine because of the daily reflections which pour in from pilots, old and young, skilled and unskilled, as they throw themselves at the challenges which arise. As long as this process continues, as long as men and women reach out to grasp at fresh experience, we can know that all is well with the future.

Most of the great flights of aviation history have been triumphs of the human spirit rather than calculated financial or political ventures.

I well remember welcoming the Russian boys at Vancouver Barracks on the completion of their pioneering flight across the pole from Moscow. Until their government officials arrived on the scene from San Francisco the Soviet airmen were exuberant spirits reveling in the personal satisfaction of their airmanship. It depressed me to see them turned from this personal glow into automatons of propaganda.

Oh, sure, the great flights are milestones of engine reliability and aircraft design and navigational develop-ments. And, sure, the oceans are conquered and the map changed and a lot of significant values thrown into focus. But to me the finest thing of all about these flights is that men can soar in spirit with no compulsion except that which springs from their own hearts.

On the following pages FLYING carries the stories of three great flights of 1953, not particularly for their news value, nor yet primarily for their excitement or technical information, but in tribute to the spirit which prompted them. But more than that... to the spirit which through the year prompted thousands of other students and pilots to get up and go on ventures of their choosing.

To some a flight around an airport is an adventure. To others a family flying vacation is a spiritual climax. To a few such as those whose story we carry the sky was the limit. And the world is the richer for them all. In these stories, then, FLYING salutes the flying fraternity.—G.R.W.

Having set three records for flying solo in a light plane, Peter Gluckmann, San Francisco’s “flyingwatchmaker,” returned home last Sunday, completing a 25,000mile flight over oceans, polar ice caps and deserts.He had traveled for six weeks to South America, across the South Atlantic, up the African coast to Europe, and over the polar route to New York.

Despite these achievements Gluckmann, a former member of Temple Emanu-El’s Emanuelites, felt chagrined because bad weather had forced him to ground his little plane in Reno and complete his history-making flight by United Air Lines.

Gluckmann is the first man to fly a light plane across the South Atlantic, the first to fly solo 2.000 miles over the African desert, and the first to fly solo in a light plane over the polar route from Iceland to Labrador.

He is now considering a solo flight to the Orient as his next adventure.

Jewish Community Bulletin, August 21, 1959, p.1

Gluckmann Set For Solo Flight Around World

Peter Gluckmann, San Francisco’s “Lone Eagle,” familiarly know as “The Flying Watchmaker,” plan to take off this Saturday (August 22) on the greatest of his solo flight exploits — this time around the world.

Noted for his series of lone flights to Europe since 1953 in a single-engine plane, Gluckmann planned to leave San Francisco International Airport at 7 a.m.

His plane is a new one — a Meyers with a 260 hp engine.

His itinerary, filed with the Federation Aeronautique Internationale to the make the flight official and eligible for the record boos, follows this route:

Mexico City, Jan Juan, Puerto Rico, the Azores, Lisbon, Cairo, Karachi, New Delhi, Calcutta, Manila, Tokyo, Honolulu and back to the starting field.

His progress will be marked as he checks in at each point with federation officials.

Successful completion of the flight will assure Gluckmann of one record, the first around the world in a light plane, and technically as second record — the first official in any type of plane. Bill Odom, Wiley Post and Howard Hughes made it in larger planes but did not register their flights for a record.

ADVENTURE: Like Old Times. TIME, December 7, 1959.

In the days of jet and rocket power, aviation's headline-getters usually fly worlds faster, farther and higher than such lonesome greats of the olden days as Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post and Lindbergh. But the airman who comes closest to matching the oldtime sense of personal challenge and adventure in the flying business is the record-seeking light-plane pilot. Last week Minnesota-born Max Conrad, 57, bumped onto the runway at El Paso’s International Airport after soloing a little Piper Comanche a nonstop 6,911 miles across the Atlantic from Casablanca in 56 hr. 26 min., thereby breaking a record in his weight class (2,204 to 3,858 lbs.).

Last spring Conrad, an ex-charter-service pilot who has logged more than 36,000 hours and more than 60 transatlantic crossings, made a Casablanca-to-Los Angeles run in the same plane with a 250-h.p. six-cylinder engine and also broke a record (TIME, June 15). This time he switched to a 180-h.p. four-cylinder engine, filled his wing tanks with 60 gal. of fuel, loaded four additional tanks (300 gal.) in the cabin and fuselage. With no supplies except three jugs of water, tea and coffee, he set out across the water.

By day he flew only 100 ft. over the Atlantic, at night he climbed to 500 ft. He made hourly radio position reports, saw no other planes or ships, never got sleepy enough to use his stay-awake pills. After 28 hours, he sighted Trinidad off Venezuela, turned up the Antilles toward the U.S., bypassing Cuba ("because I didn't want to get shot down"). He had enough fuel to make it to Los Angeles, but decided to land at El Paso because his jugs were empty and he was parched with thirst. Said he, as he downed a bottle of pop after landing: "I could have drunk a barrel of water if I'd had it."

Another member of the small company of light-plane adventurers set a record last week. Peter Gluckmann, 33, a San Francisco watchmaker, piloted a single-engine Cessna 172 from Oakland to Honolulu in 20 hr. 39 min., thus became just about the biggest man (250 lbs.) to fly the smallest plane (145 h.p.) over the longest distance (2,400 miles) of open water.

source: https://time.com/archive/6613826/adventure-like-old-times/

“The Silent Watch,” by Lt. Col Russell C Jackson about briefing of & friendship with Peter Gluckmann

The MAC FLYER, MILITARY AIRLIFT COMMAND

May 1966 pp. 14-15

by Lt Col Russell C Jackson

The man’s “modified pear shape” betrayed love of good food coupled with an aversion to exercise. Coarse blond hair fringed a perpetually shiny pate. The pale blue of his eyes contrasted pleasantly with his florid complexion. His 205 pounds tended to concentrate at the waistline and slightly below.

Nothing in his appearance suggested that Pete was "The Flying Watchmaker," chronicled in papers and magazines for his record-breaking escapades in light aircraft. But when he lumbered into our Tokyo forecast office we knew who he was. Our head office in San Francisco had messaged earlier: DALP ASSIST PETER GLUCKMANN NONSTOP TRANSPAC TRY.

My first encounter with Pete was revealing. As he approached the light table where I was tracing a forecast chart, he thrust out a strong but pudgy hand and said in soft gutterals: "Hello. My name is Peter Gluckmann. Is right, you are to make for me the weather forecasts?" Then, apologetically, "Too much trouble I hope I am not."

The storm-wracked flight he had just completed from Hong Kong had exacted its toll. Sleepless hours before and during the time aloft had etched fatigue furrows deep in his face. Dark circles underscored blood- shot eyes but a broad, happy smile dominated his features as I replied:

"Hello, Mr. Gluckmann. I'm Russ Jackson and this is Johnny Hauselt. He will help you with flight planning and general dispatch problems. The other forecasters and I will prepare your weather forecasts. We certainly don't think you'll be too much trouble."

Despite near-exhaustion, Pete insisted on briefing us on his plane, its equipment and his preliminary plans for the hazardous, murderously long trans-Pacific flight he hoped to make. Both Johnny and I were amazed at the almost total lack of navigation and radio equipment — an E6B computer, an incomplete set of aeronautical charts of the Pacific and a limited range VHF receiver and transmitter! Even the newest and largest aircraft of that era occasionally managed to get "misplaced" on flights lasting only a few hours-and they were navigated by full-time professionals and equipped with Loran, celestial navigation gear and elaborate radio aids. It was all just too much for Johnny. He exploded:

"For gosh sakes, Pete! That radio gear of yours isn't reliable for more than 60 miles at the altitudes you can hold. You'll have to dead reckon all the way from here to Hawaii unless you overhead Ship Victor or Midway. No matter how you cut it, you've got an awful lot of nothing but water to cross. Just an ordinary wind direction error or failure to hold a heading right on the button could easily put you more than 100 miles off course in the 40 hours or so it'll take to get to Honolulu. Throw in a little thunderstorm static and you couldn't read a ground station 25 miles away, even if they could read you."

When he stopped for breath, Pete put in with a. smile:

"No passengers are with me. I have done such a thing before. My compass is good. My engine is like the fine Swiss watch. No, Johnny, do not think I am to make a commercial flight. Flying is now my love and any man wants to give for his love. It is my dream to do this that no other man has done. I know I must take many chances to make this dream come true, but no family is waiting for me. Please, you have not to worry. Only I ask of you good winds and good flight plan. The rest is for me to worry. Can you do for me a minimal flight time track as your San Francisco man said?"

Johnny again pointed out that a minimal time track to Honolulu would undoubtedly miss Ship Victor and Midway Island by many miles and suggested a minimal to Victor followed by a minimal to Midway. From Midway to Honolulu, the Hawaiian chain would provide fairly frequent visual checks from low levels. Pete merely smiled again and said:

"I must get maximum distance in shortest time or I try with no hope of making the new record. Please, I wish the minimal time from Tokyo to Honolulu. I think maybe it is 35 or 40 hours to Honolulu. If possible, I like for you to give me headings to hold and for how long should I hold them. For me, winds are of not much use. Surely, I will be tired and I have no room in my cockpit to use the plotting charts. As you see, I am not a small one."

The next question about survival gear elicited the information that Pete felt a Mac West was enough. It was impossible to convince him that he should make a larger concession to commonly accepted safety practices.

"Raft? I have no room for it. Anyway, I tried already to get into a one-man raft. It refused me. If I am down, no one can know where it is I am. I will not be so easy to find as one flea on the dog's back. The Gibson Girl? She is too heavy. Shark repellent? I think they do not want to eat because I will be for a long time sweating before I come to the place where they are. Really, I take Mae West only for if I cannot get airborne because I am poor swimmer. Once I am up, it matters only to me that I complete the flight in San Francisco."

For the next two days we were busy working out practice minimal time tracks for the various low levels that Pete's grossly overloaded plane would be able to hold. At the same time, we did our best to forecast an optimum departure time, al factors considered. Pete's patience and un- failing good cheer as we tried to explain the technical processes we were going through to get the best answers endeared him to all of us connected with the planning. As the time drew closer for him to go, we found it increasingly difficult to disguise our concern about the tremendous risks he appeared to be accepting so nonchalantly. As our last preliminary planning session ended, Pete jibed:

"Well, Russ, you seem worried. Maybe you are thinking your bad forecast will make trouble for me, is it?"

Slightly nettled, I shot back:

"O.K., Pete. I'll put my money behind my forecast. This alarm watch of mine doesn't ring anymore. Take it with you, fix it and send it back to me along with the bill. Now, I wouldn't ask you to do that if I thought my winds would 'go bust,' would I? I think you're way off your rocker for taking so many chances, but you're a right guy and I hope you make it!"

The broad grin wreathed his lips again as he quickly slipped the watch into his pocket and replied:

"My work is guaranteed like my flying and your forecasts. We are both craftsmen. Your watch comes back to you in three weeks. With the help you have given me, I am already paid."

Takeoff was set for 0700 the next morning. Pete went to his hotel to get a good solid 12 hours of sleep. He planned to reach the airport only 30 minutes before takeoff, sign flight documents and get underway. My job was to complete the final fore- cast by 0430, giving Johnny plenty of time to work out and double check the flight plan and other paperwork before Pete arrived. By the time I had finished my work and had gone over the latest weather information, I'd had it! As much as I wanted to stay and see Pete off, I knew I had to have several hours of sleep before coming back to work the swing shift at 1600.

About noon the next day my wife, Margaret, roused me from blissful repose with an excited statement that Pete had been reported down shortly after takeoff. For the next two days, conflicting reports of distress calls, garbled eyewitness accounts of a light plane crash in Tokyo Bay and the usual rash of rumors came flooding over the radio and filtering into our office. Several years have passed since that genial, irresponsible guy nursed his pathetically over-burdened little airplane into the air from Haneda airport on a madcap flight that ended—who knows where? No trace of him or his plane has ever been found.

A few months later I was reading a San Francisco newspaper when I happened across a story about Pete. It gave a list of the personal effects that he had sent home by air freight the day before he took off. One of the articles listed was an alarm watch. Convinced that it must be mine, I wrote a letter to the editor of that paper giving him a minute description of the watch and relating what had happened in Tokyo before Pete took off. The editor investigated, found out that the watch was unquestionably mine and arranged to have it returned to me — still unrepaired.

Apparently, Pete had decided it wouldn't be right to take a chance of losing property that didn't belong to him. That would be in keeping with his character, as I knew him.

The basic facts of this story are true — the exact conversations changed only by time's dimming of memory. The watch is still unrepaired and it will always remain so. Every time I open the drawer of my bedside nightstand, I see it—a cherished memento of a brief friendship with one of the most unusual characters I have ever met.

But more important than its sentimental value is the unmistakable message of its perpetual silence; a clarion warning, more imperative than the loudest bell or siren, that the rules of safety cannot be violated with impunity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lt Col Russell C. Jackson, who authored this story which won Honorable Mention in the 1965 contest, is a Reservist training with Det I, 20 Wea Sq at Fuchu AS, Japan. After initial weather training and service, he was Staff Weather Officer for the 450 Bomb Gp in southern Italy, After WW II, he worked in the Far East for Pan American Airways.

Photographer takes classic plane on trip around Labrador

27 June 2017 BY DANETTE DOLLEY SPECIAL TO SALTWIRE NETWORK The Labradorian

An award-winning Canadian artist, pilot and aerial photographer flew his small aircraft to Goose Bay recently to re-enact part of a flight across North America and the Atlantic to Europe that took place 64 years earlier.

Louis Helbig lives in Melbourne, Australia. His photographs have received national and international recognition over the years.

During his recent trip to Labrador, he took photographs of the shoreline and along the Trans-labrador Highway between Forteau, Mary's Harbour, William's Harbour, Goose Bay and Wabush/Labrador City. “

I flew out over the pack ice and the icebergs and took pictures of the ice flow activity, unbelievably spectacular," Helbig said during a recent phone interview.

According to Helbig's research, a man named Peter Gluckmann famously piloted the historic two seater Luscombe (which Helbig now owns) across the Atlantic from San Francisco to his home- town of Berlin, Germany, and back, in the summer of 1953.

Gluckmann's return to Berlin was of special significance, as he had fled the city as a teenage Jewish refugee in 1939, Helbig said.

"He became a watchmaker in San Francisco ... and an amateur pilot and he bought this aircraft," Helbig said of the plane he purchased in 2013.

Helbig said Gluckmann got special permission from the American ambassador in London to fly via the air corridor, making the plane the first private, civilian aircraft to land at Berlin Tempelhof Airport after the Second World War.

It is one of few private aircraft to land in Berlin between 1945 and the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain in 1989, Helbig said. "At the time Berlin was a completely bombed-out city. It didn't get rebuilt until many years later," he said.

Until recently, Helbig said, Gluckmann's 90 hp plane was the smallest aircraft to have ever crossed the Atlantic.

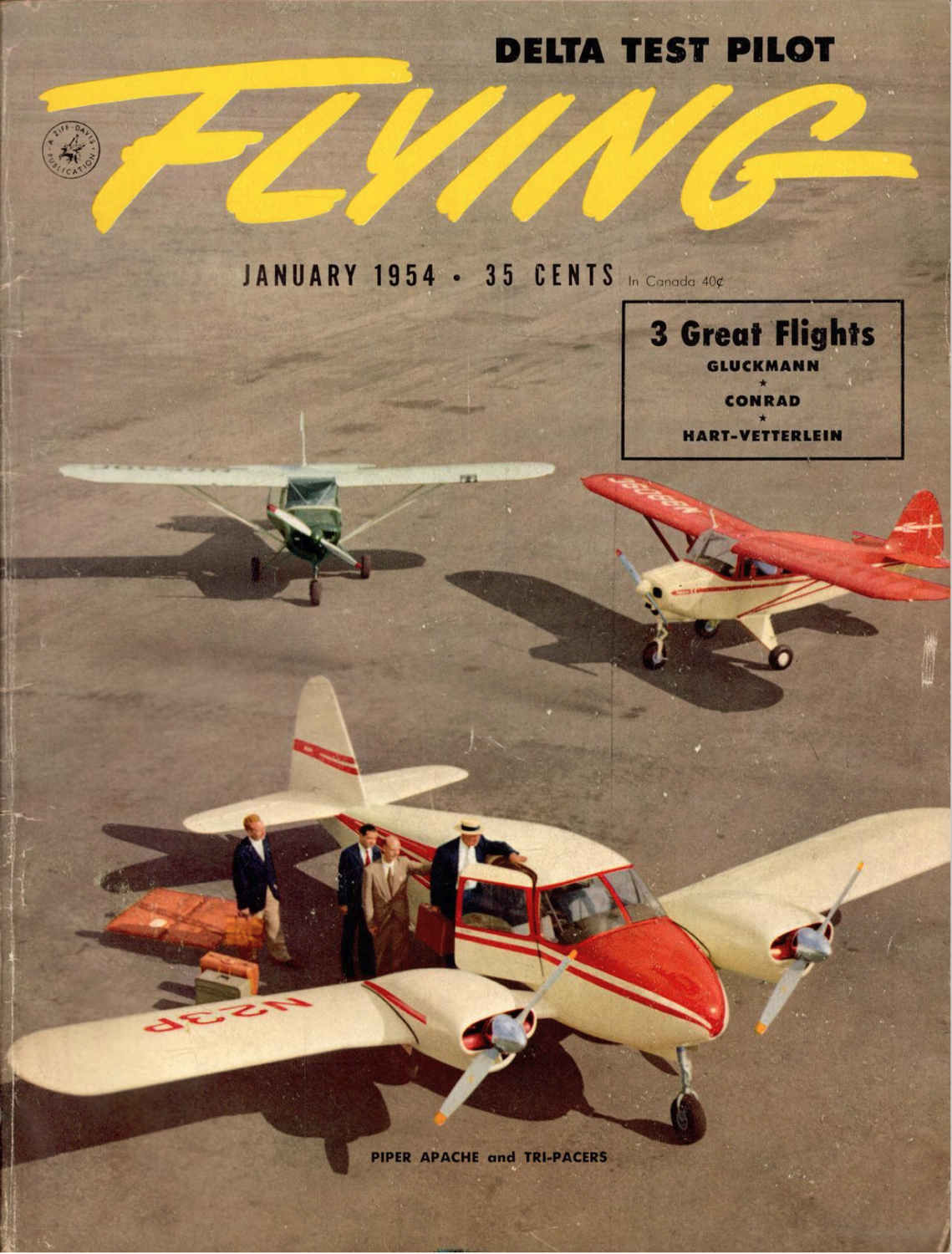

Gluckmann detailed the trip in "The Flying Magazine" in January 1954.

He ended his story by telling his readers that the only trouble he encountered was a broken wheel. He'd only changed the spark plugs twice, he wrote.

"I changed the oil twice and I must admit I never even had to tune up my motor. These little airplanes really do prove themselves dependable. If you take care of them and fly them with reasonable care, you can do anything you like with them,” Gluckmann wrote.

Six years after his flight across the Atlantic, Gluckmann set a world record for the first solo flight in a single engine plane around the world (in a different aircraft).

He and his plane disappeared into the Pacific Ocean in 1959 or 1960 while he was trying to set a long- distance record from Tokyo to the U.S.A., Helbig said.

Helbig is a commercial pilot who gets his love of flying naturally. Originally from William's Lake, B.C., his father was a pilot who also few small planes.

"The flying I do is to take my photos and do my art," he said. Helbig's recent trip to Labrador was not only to bring the plane (which now has a Canadian registration) back to where it made history more than six decades ago, but to see a part of Labrador that he hadn't already seen. (He has been to Labrador West in the past for skiing trips).

For more information on Helbig visit his website at www. louishelbig.com

A famous Jewish pilot’s vintage plane could be scrapped. This man is on a mission to save it.

Canadian Jewish News, Northstar Podcast, Oct 24, 2025 By Ellin Bessner

Louis Helbig hopes a museum will save the smallest aircraft of its time that crossed the North Atlantic Ocean.

Peter Gluckmann wasn’t a pilot by trade. But the watchmaker, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1939 as a teenager, would later become obsessed with flying. After the Holocaust, he learned how to pilot aircraft in the United States, and, in 1953, wanting to see his parents who were still back in Europe, he made history as the first person to ever successfully cross the North Atlantic solo, both ways, in a famously small plane: a Luscombe 8F.

Now that very aircraft could end up in the scrap heap—unless one man can save it.

Louis Helbig, of Sydney, N.S., bought what he’s dubbed the “Trans-Atlantic Luscombe” in 2013, and has been flying it himself ever since. But the Luscombe was damaged in an accident this summer while Helbig was flying it near Guelph, Ont. He says his insurance company wants to write the whole thing off and possibly send it to the scrap heap at the end of the month—unless he can find a way to shoulder the storage and repair costs himself.

But Helbig says the plane, and its former Jewish refugee owner, deserve better.

On today’s episode of The CJN’s North Star podcast, Helbig joins host Ellin Bessner to share stories of the plane’s remarkable past—and also his own. Helbig descends from the other side of Gluckmann’s history: Helbig’s German grandfather was a proud brownshirt with Hitler’s Nazi regime-which is why his grandson’s current mission is also partly a bit of intergenerational amends, rather than risk losing this little-known piece of Jewish history forever.

Ellin Bessner: For the last dozen years, that has been the welcome sound for Canadian pilot Louis Helbig when he fires up his antique 1948 single-engine Luscombe aircraft. When he bought the tiny two-seater back in 2013, he intended to use it for his work as an aerial photographer. But he also loved that his plane has a remarkable pedigree: for those in the know. In the aviation world, it’s famous. The Trans-Atlantic Luscombe was once owned by a German Jewish Holocaust survivor named Peter Gluckmann, who, in 1953, flew it solo, at age 27, from San Francisco, through Canada, then across the North Atlantic, to Germany. Now, he was a watchmaker, not a lifelong pilot, and he’d mostly wanted to fly in order to reunite with his parents and his younger brother, who had also survived but stayed behind in Europe. He also had it in his mind to see what had become of his boyhood home in Berlin. All that seemed quite impossible because then it was the Cold War, and Berlin was under U.S. and Russian control, and off limits to private tourists in civilian planes. But Gluckmann did it anyway.

His flying achievement was also amazing because, at the time, his plane was much smaller than the ones flown by those iconic heroes who crossed the Atlantic Ocean before him, like Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart. Louis Helbig, the current owner, lives in Sydney, Nova Scotia, and he’d hoped to keep the Luscombe airborne for a few years more. But this summer, he made a rough landing on a trip to Guelph and damaged it. It’s still there, sitting under a tarp, needing expensive repairs. Winter’s coming, and he says his insurance company is offering to write it off and likely scrap it after the end of October.

Helbig feels his plane and Gluckmann’s story both deserve a better ending. He’d love for a museum to take it. He’s tried the Smithsonian in Washington and some museums in Europe too, but so far, no dice.

He wants it to be put on display as a tribute to Gluckmann, who disappeared forever a few years after his flight, near Hawaii, flying a different plane. Helbig’s motivated also because Gluckmann’s life was linked to Helbig’s own family background: Helbig is of German origin, too and recently discovered, to his horror, that his grandfather was a Brown Shirt in Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Louis Helbig: It gives me even more, sort of, an incentive, I guess, to take this airplane as an artifact and to have it as a thing that can then foster reflection on the time that he was a witness to.

Ellin Bessner: I’m Ellin Bessner, and this is what Jewish Canada sounds like for Friday, October 24, 2025. Welcome to North Star, a podcast of The Canadian Jewish News, made possible thanks to the generous support of the Ira Gluskin and Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation.

Louis Helbig feels he’s running out of time to save his Luscombe, so he set up a website with the story of his plane, its various flights, tons of photos, and the short but dramatic life of Peter Gluckmann.

Now, Gluckmann did get some worldwide recognition. He was in Time magazine. He made headlines in newspapers from London to Australia. One article even quotes his relieved mother in London, hugging and kissing her son after he landed, but scolding him for being so overweight. Gluckmann tipped the scales at over 250 pounds, and he did some serious dieting when he got back to America to make his subsequent trips.

Louis Helbig joins me now from his home in Sydney, Nova Scotia.

It’s a great honour to have you. You reached out to us through our CJN sources with an incredible story about a plane, the Holocaust, World War II, transatlantic flight, your own piloting and aviation journey, and your own family story. And I keep telling you, there’s a book and a movie! But before that all happens, we’re going to get this story out to our audience and our listeners. So let’s talk about the plane. Describe this plane and how you got it.

Louis Helbig: Why do I have this Luscombe? Well, I used to own another version of a Luscombe called an 8A, which is the smaller engine and the like. I needed something with a sort of longer range for the photography that I was doing, and so I found this thing called an 8F, and basically, it can fly further. It has electrics and a few other sort of modern gizmos, as modern as something is from 1948. So I kind of joke, I moved up from 1946 to 1948 with my aircraft.

Ellin Bessner: How many seats, how many wings?

Louis Helbig: So the plane is very basic. It’s got two seats, a pilot seat and passenger seat.

Ellin Bessner: Side by side or one in the back and one?

Louis Helbig: No, you sit side by side. It’s a side-by-side seating, and it’s got a high wing as opposed to a low wing. It has a very small motor on the front, a 90-horsepower motor, and I can fly it, I usually flight plan, for about four hours in the air. I can fly it for a bit longer than that, actually, but sort of four hours is good and safe.

Ellin Bessner: Who’d you buy it from?

Louis Helbig: I bought it from a fellow named Richard Marcus, and he was in London, Ontario, and he, in turn, found the plane in the late ’80s in pieces in a barn or a hangar in Akron, Ohio. He bought this thing, unbeknownst, and when he went through the logs, which I still have, he realized he had the famous transatlantic Luscombe. I had never heard of this thing before that, and I was intrigued. I did a bit of research, so it has a wee bit of a rockstar following in the world of people who know Luscombes, and quite justifiably so, for having been flown across the Atlantic by Peter Gluckmann in 1953.

Ellin Bessner: Now, you said you could do four hours, and a transatlantic flight today, if you go from Newfoundland to Iceland, is that about the same?

Louis Helbig: No, no, no. So he modified the aircraft slightly, not an awful lot, but he had approximately 15 hours of flight time. So he could sit there for 15 hours and safely stay in the air.

Ellin Bessner: Except he was lower down. He couldn’t go high like we can today, and it was icing and the cold, and he could only fly low, right, in those days?

Louis Helbig: Well, yeah, yeah. So modern aviation and the big jets, Airbuses, and Boeings, they fly above the weather, but in the days of propeller aviation, you’re right in the turbulent part of the atmosphere. So you fly into clouds, you fly into ice, you fly into goodness knows what. And so, yeah, these were the kinds of hazards of navigation that existed during his time. For the most part, he flew kind of like ancient navigators used to navigate the seas. He was very good at it. He managed to, using Dead Reckoning, it’s called, get himself across from Goose Bay to a place called Bluey1, which wasn’t actually an American base anymore, but the airport in the south of Greenland. He then flew around to Keflavik, Reykjavik—there are two airports there. He flew on to Glasgow, but the weather was socked in completely, and he ended up landing another place some distance away from there, St. Andrews, I think, but I’m not actually sure.

Ellin Bessner: And this was in 1953. But let’s stop and go back a little bit. So you have this guy’s plane. You don’t really know much about him. What have you then learned about who he was and how he came to do this and where he came from.

Louis Helbig: So, a bit like the other aviation gigs, I was intrigued by the transatlantic story. Right. There’s a lot of risk associated with that. The fellow was brave! I mean, albeit in 1953, the plane was only five years old. You know, now it’s much older and what have you, but still, it’s just amazing what he did as an aviation accomplishment! As I dug some more, I learned that he was a refugee. He was a Jewish refugee from Berlin, and his family fled Berlin in 1939, as best as I can ascertain. They fled to London, which I know was very late for many people to get out of Germany. His family stayed in London, and then he emigrated in 1947.

Ellin Bessner: It was like 12 when he escaped Hitler.

Louis Helbig: Exactly. He was almost 13 years old.

Ellin Bessner: So he would have had his bar mitzvah.

Louis Helbig: Yeah, just at that age. Yeah. And so off he goes to the States.

Ellin Bessner: Wait, so after. Hang on, he goes to the States after the war 1947. So they ride out the war. They were interned, some of them, because they were enemy aliens. The British didn’t didn’t treat German Jews well, even if they were the actual victims. They thought they were the Fifth columnists [spies]. And they got interned and released in 1940. His father was an electrical engineer, I think, and his mom, I don’t know what she did. And then there was a brother as well, William.

Louis Helbig: There’s a brother as well too. So I have one photo from the press clippings I found. It’s a brother, William. They’re standing in front of a different plane a few years later. And there’s brother William along with the mother and the father.

Ellin Bessner: They were all grown up by that. So he basically waited. He waited until the war was over. He went to San Francisco to seek his fortune.

Louis Helbig: That’s right.

Ellin Bessner: He didn’t stay in London.

Louis Helbig: Yeah, that’s right. So he emigrates in ’47. He ends up in San Francisco within weeks or days. He opens a shop. It’s on Lick Avenue, I think it’s called, in San Francisco. Then he gets an exception to learn how to fly an airplane because as an alien you weren’t allowed to get a pilot’s license apparently in the States at that time. Sometime after that, he buys this airplane and then he gets this idea that he can fly over the Atlantic to visit his parents.

Ellin Bessner: Who are in London, who he hasn’t seen in years. Right.

Louis Helbig: That’s six years he would have not seen them. Now, bizarrely, compared to how much it costs to fly in a commercial plane nowadays, he figured it was going to cost him less to fly his airplane to London this way than if he was to fly or take the boat or whatever to get back to London. So I think he estimated it was going to cost him $300, and all told, it cost him about $400 for fuel, lodging, and meals or whatever.

Ellin Bessner: But how did he get permission to do this? It was the Cold War. Who gets to fly a private plane into all these places? That’s the most interesting thing. Is it luck or perseverance? He got to London and then he continued on into the Cold War part of Europe.

Louis Helbig: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So there’s one eyewitness account I’ve got, there was one person who was there in Goose Bay at the American base at the time; it was an American base, and they told him he couldn’t fly across and he said, “Oh, well, then I won’t.” Then he gets in the plane, he takes off, and he goes off in the direction he wants to go to, opposite to what he said he was going to do.

So I think he just went ahead and did it. After that it sort of normalized, I suppose. At one point he mistakenly lands at some top secret base which might have been Boscombe Downs. He gets lost and in an article he says, “My goodness, it was embarrassing to lose his way in the last few hundred miles of flying down to London.” But. So that’s one layer of this. But of course, 1953, we are in the midst of the Cold War. In ’48 and ’49, the Russians blockaded Berlin and there was the famous airlift. So that’s sort of hanging in the background. Just as he’s flying across, there is the East German uprising against the Russians. That happens on June 17, 1953. That has just happened in the background. So that would have been the news when he got to London. Anyway, he gets to London, there’s this beautiful picture of him hugging his mother. His mother is not impressed, but he.

Ellin Bessner: Didn’t hang around for that long. He stayed for a while and visited his mom and saw where he grew up. Then he wanted to fill a bucket list to go back and give, what, a middle finger to Hitler and go back to Germany? And he gets there?

Louis Helbig: That’s right. I don’t know if how many people still remember this. I suppose so much has happened, but Berlin was an occupied city until 1989. Technically until 1990. Right. It was occupied by the Russians, the Americans, the French, and the British. West Berlin was where the French, the British, and the Americans were. So technically it wasn’t really part of Germany. And so right at the end of the war and then in the Cold War, it was extremely fraught to get into the place. So here he goes, he goes to the ambassador, the American ambassador in the UK, and he gets permission, he gets a letter of permission that he can fly to Berlin, Tempelhof. Berlin Tempelhof was the centre of the Nazi aviation. Yeah, it was their showpiece. And off he goes. He flies to Hanover. He lands at the American base there. The base commander looks at him and says, “You’re not going there. No, there’s no way. There’s no way you can do that. No one’s done that. You will not get permission.” And lo and behold, he pulls his letter out and the commander says, “Well, I guess you can go.” And off he goes. He flies into Berlin Tempelhof, which is just amazing. So he certainly is the very first private civilian aircraft to land in Berlin. It’s also very likely the only private civilian aircraft that landed there.

Ellin Bessner: So why do you think he wanted to go to Berlin so badly?

Louis Helbig: I think there’s a bunch of things. One is this pull to go home. Like, he grew up there, he had his house there, he had his friends there, he played on the streets.

Ellin Bessner: Right. But there was the Holocaust and all the friends were probably gone and deported. Or Kindertransport. Or balmed by the Allies.

Louis Helbig: Yeah, So he has that. He goes back. I think of the bit of the “Sunken Villages” project I did, where people have had their homes removed from them. They have no place to go back to. They can’t Google their address and go back to the place because it’s gone. It’s now underwater.

Well, in some ways, the same thing for Peter. He goes to where his house was. His house is gone. It’s not even there. There is some rubble, which. Berlin in 1953 was still absolutely in rubble. People were still growing potatoes and carrots and what have you in between the rubble kind of thing to get by. And he goes to where his house was, and it’s just gone. It’s just gone, period. You know, it’s just. Think of that. Think of the. And think of all the people who were there, who he would have known. His friends, his cousins, they’re gone, too. But in the other part, that really comes across as, he was very fascinated by what was going on with the Cold War. And then he flies home.

Ellin Bessner: And he got a hero’s welcome. His synagogue, the local mayor, the Time Magazine. Like, he was a big celebrity around the world and not only in aviation.

Louis Helbig: Yeah. So then, as best as I can piece together, he then wants to go back and fly out again. So, I now know that he tried flying the same plane across the Atlantic again. And he flew out to Gander in Newfoundland. And the Canadians told him, “You’re not flying.” Maybe there were already rules, or maybe there were new rules. And so he hopped on a commercial plane. At that time, that wasn’t a big deal because all the planes landed in Gander to fly onwards. That was just the way it was. And so, he left his Luscombe in Gander and he went to see his parents in London and did whatever he did. Then he buys himself a different airplane called the Cessna 190. And then another little tidbit, he flies the very first airplane to fly from Israel to Egypt. It’s the very first actual flight between the two countries.

Ellin Bessner: All right, Louis, so we have to understand, what do you feel about him now that you know him, you’re in his plane. What connects you to him when you think about this?

Louis Helbig: Well, for one, it’s just simply being in the same space. I went to Goose Bay with the airplane, so I’ve flown there, landed there. When I landed there, I couldn’t resist, and I said, “Oh, this is the plane. This is, you know, this happened in 1953 and what have you.” And oh wow, that’s really cool. There was chit-chat on the air traffic control. So there’s that. There’s this idea of being in the same space. It just seems incredible, sort of a pinch-me kind of thing that you could be in the same little tin box of an airplane. And that’s what he looked to. The panel he put into that airplane is more or less still there. The paint on the inside is what the paint was when he had it. There’s a lot that’s very similar, I think, about what he might think about what I’m doing and with it. And I put myself in his boots in terms of what, you know, what he did.

But the other part that really intrigues me is we have, in some senses, a similar background and a very different background at the same time. So, I’m of German ethnicity, I speak German, and there’s a German phrase, a word called zeitzeugen. So to be the witness to your time. And he is a witness to incredible things. He is a victim; he is a witness to. He survives, his family survives, at least part of his family survives, his immediate family. And he goes back to what he was pushed away from. He’s also entirely drawn into the whole Cold War thing as well, too, in terms of what he sees and what he experiences. There’s something there sort of essential; there’s something profoundly human about what he’s doing and he’s pushing boundaries in himself. He’s got certain dreams, if you will, about what he wants to do and he acts on those. And he does that with this little airplane and later on with his other airplanes as well, too. And it’s not just a sense of adventure or whatever that’s. I think that’s too trite. There’s something more going on there in terms of what he’s doing, what he lives through, what he does, how he perseveres. And then he feeds off a bit of the fame that he gets as well too, as it goes along. So that sort of helps and he’s able to make something of a living, I think, from some of the things that he’s doing as he gets to be sort of more well known and famous. But the essence of it is kind of like there’s something magical about being in the air.

Ellin Bessner: You mentioned you had family in the area where he landed. So I need to ask you how, as the descendants of Germans who are not Jewish, that your family perhaps were part of the Nazi or German government regime? Brownshirts. How do you navigate? And I don’t mean the pun, but how do you do both, being the grandson of someone who were the perpetrators of this story that you’re telling of a German Jewish Holocaust survivor who escaped to, as you just said, do great things?

Louis Helbig: Hmmm. You know, that’s a tough question. I think that one of the reasons why I am so keen on Gluckmann’s story being told and the aircraft being used as an artifact at a museum is that it opens the door to exactly these kinds of difficult, contradictory questions and, you know, where we can reflect on things. So on my paternal side, there was no cooperation with the Nazis. There was no relationship there at all. They were urban, bourgeois people who were very skeptical, as I think a lot of people in Berlin were very skeptical and resistant to the Nazis.

But on my maternal side, much to my horror, I discovered this evidence that shows very clearly that my grandfather was a Brown Shirt. He marched around and, you know, full on, Heil Hitler. And he ran a bookstore slash stationery store. And there’s a picture on Hitler’s 50th birthday of, you know, all this stuff in it, you know, with him and my grandmother standing in front, you know, proud as punch. And it just. It makes me so. When I learned this a couple years ago, I wasn’t thinking of Peter Gluckmann or anything. I was just shocked and appalled that that was part of my past. And I couldn’t believe it. I was just categorically shocked that I didn’t know that that existed. I had no sense of that within my own family and my own family connections of any, you know, any celebration of that sort of thing. I’ve always heard about the war as being this horrific thing where, you know, family members died, there was deprivation, all these horrible things, and I’ve never heard anything else within my own family. It was shocking.

Ellin Bessner: And so what does telling Peter Gluckmann’s story do for you? How does that bring you to a new place with. You mentioned processing?

Louis Helbig: That’s a great question. I’ll go back one step further and just talk about my work as an artist. So what I’ve done in the past is I create these images, often very abstract aerial photos, some of which were taken from this airplane. And I put them in front of people in exhibitions or in my book or what have you. And then people engage with these things and they say, “Oh, that’s an art, it’s a piece of art,” or whatever, and it opens a door then to reflect on what it is that they’re seeing and whatever they feel about it, implications they might have personally or broadly, the environment, climate change, whatever it might be, doesn’t matter. Like, they own it and they can think about it.